by Lucy Dayman: A practice in appreciating simplicity, Zen art grew up around the philosophy of Zen Buddhism.

Despite its religious underpinnings, the impact and evolution of the form traverse both spirituality and everyday culture.

Despite its religious underpinnings, the impact and evolution of the form traverse both spirituality and everyday culture.

In Japan, where Zen has long been entwined in the cultural DNA of the nation, painting and calligraphy became two important vehicles for spreading the message of Zen masters to their students. An amalgamation of spirituality, education, culture, and creativity, Zen art is at times difficult to articulately classify, but is infinitely fascinating. From the history, key artists, essential locations and its modern rebirth, here’s a crash course in everything Zen art.

What is Zen Buddhism?

The evolution of Zen Buddhism in Japan is a topic about which numerous books have been written. Given the profound and far-reaching influence of Buddhism in Japanese life, there’s no way to do it justice in one article. However, some context is essential for those interested in Zen art.

Tsuba Sword Guard with Figure of Daruma, 18th Century, Met Museum

Zen is just one of many sects of Buddhism. The sect known as Chan was the creation of Buddhist monk Bodhidharma, who came from India and later settled in China. It’s thought that around the 7th century Chinese Buddhist missionaries introduced Chan to Japan, where it became known as Zen. Meditation, also known as zazen is at the core of all Zen Buddhist philosophies. Followers believe meditation leads to self-discovery and enlightenment. Essentially, without meditation, there would be no Zen.

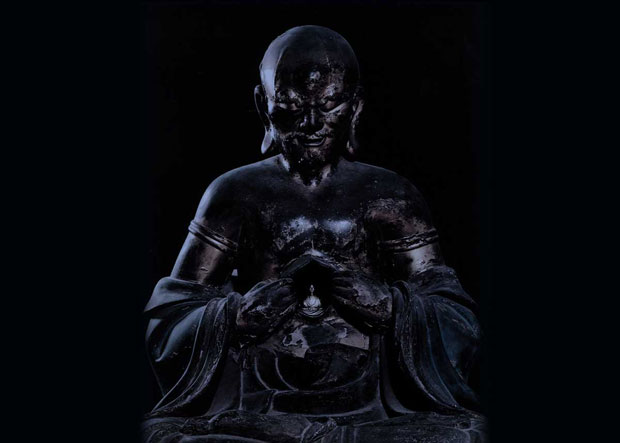

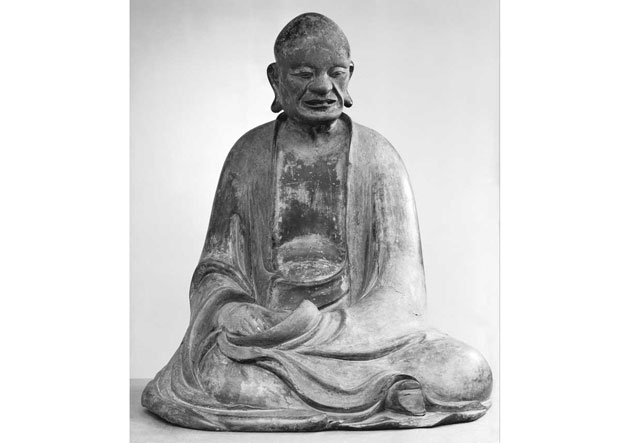

Wood and Lacquer Statue of a Rakan or Englightened Person, 17th Century, Met Museum

Zen Buddhist philosophy strongly follows the idea that that self-centric thinking or ego is detrimental to enlightenment, keeping one entrapped in the human world. To free oneself from this world, Zen practictioners meditate, clearing their minds of superfluous thoughts and freeing themselves from human shackles.

What is Zen Art?

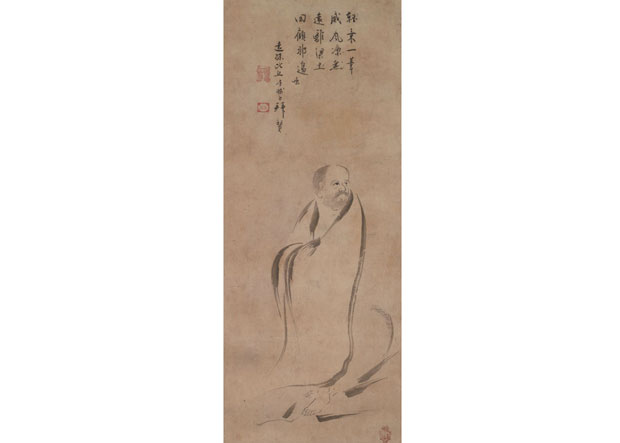

Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi River on a Reed, Kano Soshu, 16th Century, Met Museum

The barriers between human existence and reaching enlightenment are the primary catalyst for so many works of Zen painting. This is epitomised in the historic piece Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi River on a Reed, by artist Kano Soshu (1551–1601). An elegantly simple ink illustration of Buddhist monk Bodhidharma (known in Japanese as Daruma), the image carries with it the mentality that you don’t need extravagance to have a meaningful existence. Less is more!

Old Plum, Kano Sansetsu, 1646, Met Museum

Although Zen prizes simplicity, the art of Zen isn’t always minimalistic in style. Iconic artist Kano Sansetsu’s visual outputs were incredibly bold. His four sliding-door panel painting Old Plum (1646) was once part of Myoshinji temple’s sub-temple Tenshoin in Kyoto. Featuring the thick, black, twisting trunk of a plum tree, this work would have once been the backdrop to a Shoin Room, a room used for study in a Zen monastery.

Old Plum, Kano Sansetsu, 1646, Met Museum

At first Zen art typically represented religious figures, but as the time passed, more secular imagery was explored, and bamboo, flowering plums, orchids were some of the regularly featured motifs.

Zen and the Art of the Tea Ceremony

© Mizuno Toshikata, The Tea Ceremony, 1900s

Zen isn’t all just about meditating and studying though, the tea ceremony is another manifestation of traditional Zen culture and art. Before it became popular in Japan, many Chinese Chan monks would drink tea to stay awake during long sessions of meditation. When in the 9th century Buddhist monks travelled to China to study, they brought back with them tea leaves and a fresh way to brew it; mixing hot water and ground up leaves with a whisk. This was the beginning of the Japanese tea ceremony.

Ceramic Teawear, Musée des Beaux Arts de Lyon

The version of the traditional Japanese tea ceremony we see today was created by a former Zen monk, Murata Shuko, who called the practice wabi-cha (wabi in Japanese is an appreciation of both simplicity and the transience of everything). This practice is immortalised in the creation of tea ceremony ceramics. Typically utilising elegantly simple earthenware cups, vases and bowls; the tools used for the service are a practical, physical embodiment of the Zen philosophy.

Zen Buddhism in Classic Japanese Art

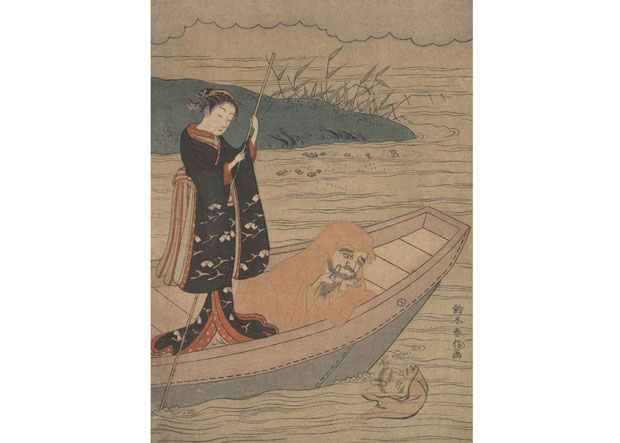

Daruma in a Boat with an Attendant, Suzuki Harunobu, 1767, Met Museum

Ukiyo-e, Japanese woodblock prints, is one of Japan’s most famous art forms and one we’ve covered extensively in previous articles (such as Hokusai’s Iconic Images of Mount Fuji). Given its ubiquity on the art landscape, it’s a not a surprise that many impressive works of Zen Buddhism exist in this form. One highlight of this art form is Daruma in a Boat with an Attendant by Suzuki Harunobu (1767).

What makes this piece worth mentioning is its visual message. Quite unlike what we’d expect from Daruma, the founder of Zen Buddhism, to be like, this image sees him plucking hairs from his chin in a display of complete vanity. Ukiyo-e artists have long had a reputation for producing works with that throw a critical eye on cultural norms and expectations, and the hypocrisy of society. Daruma during the Edo-Period became a slang term for a courtesan, while the word darumaya meant a brothel; this image is a play on those concepts.

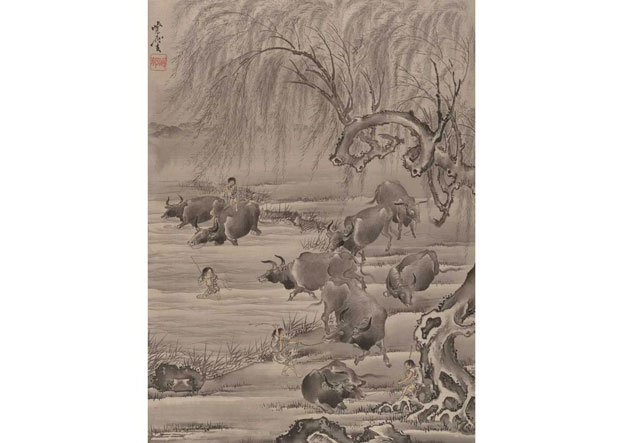

A century after Daruma in a Boat with an Attendant, Kawanabe Kyosai created Buffalo and Herdsman, a stunning interpretation of the Buddhist parable Ten Scenes with an Ox. In this story, an ox is found by a boy (who is meant to represent religious training), who ropes the beast and leads it on the right path home (or to ‘enlightenment’ for those reading between the lines).

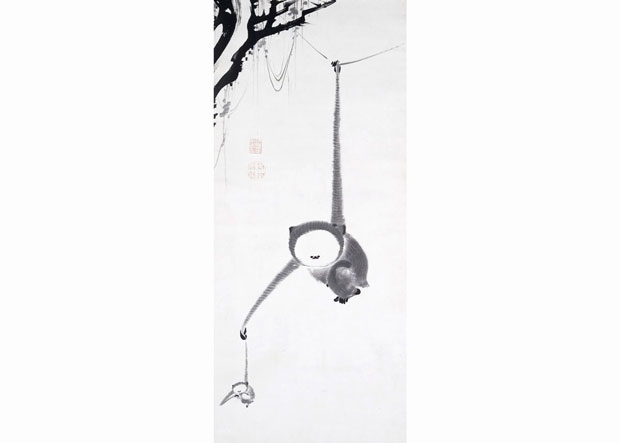

One other reason why Zen Buddhist art is so popular and admired is that these ideas of Zen Buddhist philosophy are often best described through imagery as opposed to written form. Take Two Gibbons Reaching for the Moon (1770) by Ito Jakuchu as an example. The image is an analogy for the bad human habit of trying to attain the unreal (the unreal here being the reflection of the moon in the water), when what we should be after is spiritual sustenance.

Zen and Modern Art

© Shiko Munaka, Samantabhadra, National Gallery of Victoria

Although its history goes deep, Zen art and design isn’t suspended in time. Even if its philosophies are about reaching beyond the human physical realm, the artists that created the work are still influenced by the very human field of modern art.

One of the best examples of the form’s transformation is Shiko Munakata’s woodblock prints. Munakata was generally regarded as the greatest woodblock printer of the twentieth century. His Ten Great Disciples of Buddha (1939/1948) series saw traditional spiritual themes reimagined in a folk art form with an almost Picasso-esque, modern, cubist perspective.

Where to See Zen Buddhist Art?

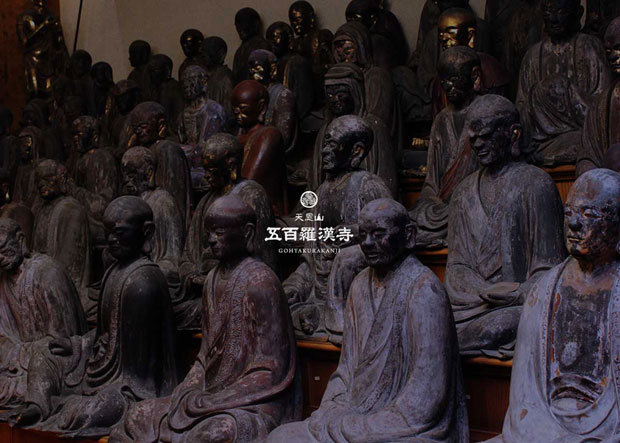

1. Gohyaku Rakanji, Tokyo

One of the most incredible Zen experiences you can have in Japan is paying a visit to Gohyaku Rakanji in Meguro. Here you’ll meet hundreds up hundreds of Rakan ascetic beings who take care of the rules of Buddhist law here on earth. Crafted over a decade, monk and sculptor Shoun Genkei created 500 of these figures, many of which you can still admire today.

Address: 3-20-11 Shimomeguro, Meguro, Tokyo (see on Google Maps)

2. The Museum of Zen Culture and History, Tokyo

© The Museum of Zen Culture and History

If you’re in Tokyo and want to learn more about the evolution of the art, be sure to pay a visit to The Museum of Zen Culture and History. Part of Komazawa University, the museum is open to the public and houses both temporary and permanent exhibits covering all facets of Buddhism, including of course Zen art.

Address: 1-23-1 Komazawa, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo (see on Google Maps)

3. Nanzen-ji, Kyoto

Scenes in and around the Capital, 17th Century, Met Museum

In Japan’s most famous historical city, Kyoto is where you’ll find Nanzen-ji. Founded during the 13th century, it was an influential icon of the popularization of Zen Buddhism across Japan. Known as one of the most stunning temples in the city, its intricate design, and rock garden, has made it a must-visit destination for those exploring Kyoto’s connection to Zen, which is perfectly captured in the six-panel 17th century image Scenes in and around the Capital.

Address: Nanzenji Fujuchicho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto (see on Google Maps)