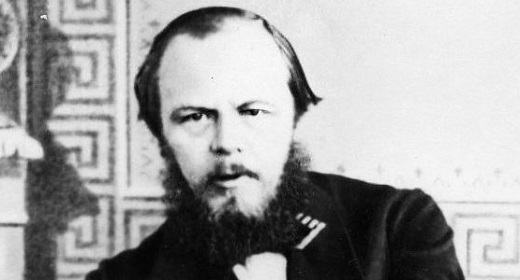

by Dr. Howard Markel: Saturday, Nov. 11, is the birthday of Fyodor Dostoevsky, one of Russia’s greatest novelists…

The author of such classics as “The Brothers Karamazov,” “The Idiot,” and “Crime and Punishment,” Dostoevsky was also one of the most famous epileptics in literary history.

In his biography, “Dostoevsky, 1821-1881,” E.H. Carr uncovered a doctor’s treasure trove of evidence documenting Dostoevsky’s epileptic seizures as a young man, especially during his student years, 1838 to 1843. One of these episodes included a rather serious, generalized tonic-clonic (or grand mal) seizure in 1844, which was observed and described by several of Dostoevsky’s friends. During his 20s, the novelist recorded several “journal descriptions” of what appear to be simple partial seizures. He also described how certain triggers, such as the lack of sleep, alcohol consumption or overwork, brought on his seizures.

Contemporary observers recorded more episodes during the 1840s, when Fyodor appears to have been stricken by several seizures of different types. Most famously, in 1849, he was diagnosed with epilepsy shortly before being taken to a Siberian prison in Omsk. He was sentenced there to four years of forced labor for espousing Socialist beliefs. His seizure activity only worsened during his imprisonment, and by 1853, he was quite debilitated from epilepsy as well as a series of mental health and physical ailments.

During his last decades of life, epilepsy continued to affect his life, work and output. Fortunately for literature lovers, in 1880, he was able to finish his masterpiece, “The Brothers Karamazov.” He died in 1881 after multiple bouts of bleeding from his lungs, most likely caused by tuberculosis.

Interestingly, not every doctor has agreed that the novelist suffered from epilepsy. For example, in 1928, Sigmund Freud, the famed psychoanalyst and neurologist, penned an essay, “Dostoevsky and Parricide,” in which he argued that the novelist’s seizure disorder was merely a symptom of “his neurosis,” which “must be accordingly classified as hystero-epilepsy—that is severe hysteria.”

Today, many neurologists have refuted Freud’s psychogenic claim and have retrospectively diagnosed Dostoevsky with cryptogenic (of no clear cause) epilepsy of probable temporal lobe origin (the region of the brain where his seizures seemed to originate; temporal lobe epilepsy is one of the most frequently diagnosed forms of epilepsy and is notable for frequent, unprovoked focal or complex-partial seizures).

Like many great writers, Dostoevsky wrote about what he knew and how he experienced the world. Not surprisingly, many of his characters suffered from epileptic seizures. For example, he mentions the disease in his 1847 story, “The Landlady,” where an old man named Murin experiences a seizure when he attacks the story’s protagonist, Ordynov.

What is interesting about this description and those that follow is that they do more than merely note a trembling of the body or a loss of consciousness. Dostoevsky describes many of the cardinal symptoms of various types of seizures even down to the sensory auras and the sense of déjà vu many epileptics experience before a seizure and the intense fatigue they often feel after one.

Like Charles Dickens, Dostoevsky (who was a huge Dickens fan) eschewed cliché descriptions of diseases for his fictional world and worked hard to make sure he got the symptoms and disease patterns correct before committing them to the written page.

Epilepsy and seizures appear elsewhere in his work including his 1861 serial story “Insulted and Injured,” which features an abused orphan girl with violent epileptic seizures or “fits.” Dostoevsky also describes characters with seizures in his novels “The Idiot” (1868) and “Demons” (1872).

But the Russian novelist made the most famous use of his neurological illness when creating the illegitimate son Smerdyakov in “The Brothers Karamazov.” Smerdyakov, it may be remembered, suffers from epileptic seizures for most of his life. He murders his father Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov and creates a series of alibis that he ties to several imagined seizures. Smerdyakov later commits suicide but not before framing his brother Dimitri for the father’s death.

There were points in his life when Dostoevsky wrote he was grateful for his seizure disorder because of the “abnormal tension” the episodes created in his brain, which allowed him to experience “unbounded joy and rapture, ecstatic devotion and completest life.” At other times, the author regretted the disability because he thought it had wreaked havoc with his memory.

Good or bad, useful or not, epilepsy framed Dostoevsky’s life as tightly as the “Superman” or Ubermensch philosophy seemed to frame the life of “Crime and Punishment” main character Raskolnikov. What remains so remarkable about this 19th century writer is that he was able to create such great art out of his disability rather than allow his disability to define or defeat him.