by Chris Taylor: As America experiments with decriminalizing psilocybin, one scientist spreads the gospel of ‘shrooms at festivals — and in ‘Star Trek’…

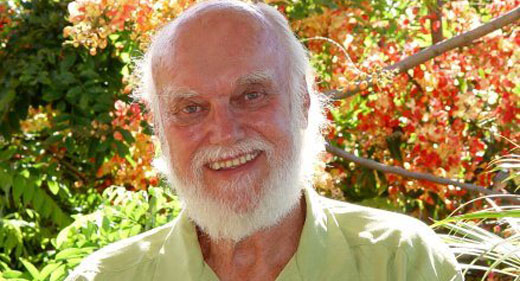

It’s an almost-too-warm California spring morning at Lightning in a Bottle, one of the preeminent music festivals for eco-conscious, EDM-loving millennials. You’re under shade, mercifully, chatting in camper chairs with an older guy with a big bushy salt-and-pepper beard. He wears round specs and a utilikilt, and talks real fast. The conversation starts with the guy talking about how he was the influence for a major character in the latest Star Trek show.

“I was in the woods, building a cabin in the shape of the Starship Enterprise,” says the guy in the kilt, “and then I got this call from CBS and they said ‘listen, a bunch of writers from Star Trek want to talk to you, they’re really stuck, do you have any ideas?’ I said, ‘turn on your tape recorder.’” He gave them so many ideas, he says, that they named a character after him.

Uh huh, you might think. Riiiight.

Indeed, it soon becomes clear that ideas are in no short supply with kilt guy. The conversation veers through half a dozen of them at hyperspeed. The idea that a universal web of dark matter, plus our more familiar World Wide Web, plus the human brain, all mimic the “mycelial networks” of mushrooms under our feet that bind and feed all of Earth’s soil. The idea that this network, an enormous mass of fungus that branches and communicates underground, is in some way sentient. The idea that human brains went through an evolutionary growth spurt after we encountered poop-grown psilocybin (“magic”) mushrooms on the savannah of Africa.

The flurry of ideas suggest that mushrooms could not only cure many diseases (just like penicillin, derived from a fungus) and depression, clean up industrial waste and oil spills and save the bees, but they can also store carbon in vast quantities underground, and thus save us all from climate change.

By this point, you may be wondering whether kilt guy has just ingested a heroic dose of magic mushrooms himself. But he hasn’t (well, not on this fine morning, anyway). This is Paul Stamets, internationally-renowned mushroom expert, and yes, a man who bequeathed his name and ideas to a lead character in Star Trek: Discovery (Lt. Cmdr. Paul Stamets, played by Anthony Rapp).

The Stamets Singularity: Lt. Paul Stamets (Anthony Rapp), himself based on mycologist Paul Stamets, meets mirror universe Paul Stamets among the interstellar mushroom spores in ‘Star Trek: Discovery’

CBS

Stamets has been credited with discovering four new mushroom species and holds eight patents. One of them, for a mushroom-based pesticide, could reportedly upend Monsanto’s business model. He has worked with the Pentagon (on mushrooms that cure tuberculosis) and rocked the mic at TED (a 2008 TED talk, viewed more than 5 million times, is the reason Star Trek producers called him in the first place). He’s a character in a bestselling book, an author of five books himself, and an old friend of “Optimum Health” guru Dr. Andrew Weil.

“Oh yeah,” one festival attendee said when I mentioned his talk, “I follow him on the ‘gram.” (Stamets has 181,000 followers on his regularly updated Instagram feed.)

He’s also a hero to a new generation of activists who this year successfully decriminalized magic mushrooms in Oakland and Denver, and are taking aim at 60 more major U.S. cities. When Stamets talks, you can hear our drug-friendly, consciousness-expanding future barreling down like a freight train.

Because for every outlandish idea that grows in his mind like fungus, Stamets brings the receipts. “His extravagant claims for the power of mushrooms are bound to set off a journalist’s bullshit detector,” writes author Michael Pollan in How to Change Your Mind, his 2018 book on psychedelics, which features an eye-opening chapter on Stamets. “Yet even some of Stamets’ airier notions turn out to have a scientific foundation beneath them … Stamets’ ideas and theories have turned out to be far more durable, and more practicable, than I ever would have guessed.”

(For his part, Stamets says he enjoyed his time with Pollan, but also pokes fun at his book for being scientifically basic — dubbing it “What I did on my summer psychedelic vacation.”)

While on stage in front of hundreds of festival goers at Lightning in a Bottle in May, he runs through a presentation filled with screenshots of dense scientific papers. He never uses an English name for a mushroom when a Latin one will do. As a science educator, he makes Bill Nye look like Big Bird. But the science in question is so jaw-dropping, it cuts through even the sleepiest stoner’s festival haze.

At the conclusion of the talk, Stamets unveils the recent discovery that male cicadas fly around with their asses covered in mushroom spores. The mushroom in question isn’t psychedelic, but it does seem to manufacture both psilocybin and an amphetamine when it’s on a cicada butt. We don’t know why or how, exactly, and when you follow the research it’s pretty terrifying. The spores turn the cicadas into sex-crazed zombies while simultaneously castrating them. Their butts literally fall off, spreading spores far and wide in the process.

But Stamets digs out a fascinating detail — the infected cicadas imitate the female mating call, causing more male-on-male mating — and quickly pivots to the point that psilocybin simultaneously makes us friendlier, more “feminized,” less aggressive and more courageous, desirable qualities both in a mate and in a leader. He gets a standing ovation from his tatooed, pierced, dreadlocked audience.

If this all makes Stamets sound like the Timothy Leary of ‘shrooms, “crashing around America selling consciousness expansion for three bucks a hit,” to use Hunter S. Thompson’s famous put down of the LSD-pushing former Harvard psychologist — well, that’s not really the case. First of all, Stamets will never give you a dose of psilocybin himself. He’s still wired by paranoia from his days as a DEA-licensed mushroom researcher, worried that anyone could be a potential undercover DEA agent.

He’ll just tell you what parts of the forest in which to find it, how not to mistake it for poisonous mushrooms, and how to store it. His current favorite system involves crushed mushroom juice in ice. (“Ice cubes are great for Burning Man,” he says, deadpan.)

Secondly, a big portion of Stamets’ spiel, even here among a highly receptive crowd, is about telling people that it’s a profoundly good thing to treat mushrooms as sacred — and thus severely curtail the amount they ingest. He will note that psilocybin has proven effective in the treatment of PTSD, but will also point to a study that shows mice recover from traumatic experiences faster if they take a smaller dose. He will strongly suggest that anyone disposed to take it should “stack” it, in the terminology of drug makers, with the B vitamin known as niacin — partly because it helps unlock the effects, partly because niacin makes your skin flush at high doses, so you don’t want to take too much.

Stamets’ cautious approach to his wonder drug has also infected the movement now pushing for its decriminalization — when it, too, could have gone in the Timothy Leary direction. (He also hates the word ‘shrooms.)

THE MUSHROOM PARTY

Decriminalize Nature Oakland celebrates its success at Oakland City Hall. Carlos Plazola is fifth from right.

In October 2018, a former chief of staff to the Oakland City Council president named Carlos Plazola, unaware of Stamets’ advice, took what he calls a “heroic dose” of psilocybin mushrooms, then asked his cousin to lock him in his bedroom for five hours.

Luckily, Plazola had the best possible outcome: a life-changing trip. “There was before, and there was after,” he says now. His immediate epiphany: “This needs to be available to people who suffer from trauma and self-annihilating thoughts.” Unlike most ‘shroomers, he had City Hall connections.

More lucky still, then, that last December Plazola hooked up with a so-called “sacred garden,” a ‘shroom-friendly group in Oakland that included some old friends of Stamets’. Together, they talked about how they would pitch decriminalization to the City Council. Caution, Stamets-style small doses and education were emphasized. Plazola read up on Stamets.

In January, Plazola became co-founder of a new pressure group, Decriminalize Nature Oakland. The same month Stamets spoke at Lightning in a Bottle they swayed city officials during a hearing at City Hall, winning the attention of a packed house.

“They were not a bunch of hippies; they were doctors, lawyers, nurses, scientists,” says Plazola. He’d chosen the timing just right: Not only had the success of Oakland’s cannabis industry helped pave the way, but Denver — the OG legal pot city — had just narrowly voted to decriminalize mushrooms via a similarly loosely Stamets-connected campaign. (The election had happened the week of Stamets’ Lightning in a Bottle talk, lending the affair the air of a victory celebration.)

Oakland City Council was predisposed to agree — and in Trump-era California, the time was right to do something bold and progressive. Councilperson Noel Gallo, a friend of Plazola’s, promptly introduced a motion to direct police resources away from chasing down federally illegal psilocybin.

“Growing up in the streets of East Oakland, Mexican families couldn’t afford Walgreens,” Gallo recalls. “My grandmother was a healer. She had native plants that helped you with the flu. It always worked for us.” (Indeed, Tamiflu is made with the acid found in oyster mushrooms). Gallo also has a nephew who went to Iraq and needs medication for his anxiety.

It was time, the police chief agreed. Gallo was taken aback. “I thought I was going to get a stronger negative reaction,” he says. The motion passed in June. Now Gallo is in the second stage of the process, where he and other council members talk about how Oakland can implement its newfound respect for a plant that may be more powerful, and more versatile, than marijuana.

“Down the line, in a few years, our dispensaries may not just be for cannabis,” Gallo says. “They are places that meet physical and spiritual needs.”

Criminalized nature: Police in Orange County, California remove a jar from a psilocybin mushroom-growing “drug lab” in 1998.

DON KELSEN/LOS ANGELES TIMES VIA GETTY IMAGES

Meanwhile, let’s pause to admire the fact that Plazola got this whole citywide legal and cultural shift enacted in less than a year after taking his life-changing ‘shroom trip. Many of the psychedelically experienced dream of doing such a thing; he actually made it happen.

And now he’s helping other cities do it, too. Plazola says Decriminalize Nature Oakland is consulting with like-minded activists — not just in nearby San Francisco, Berkeley, and Santa Cruz, as you’d expect, but in 60 more cities across the U.S. “We have a Slack channel and webinars every 2 weeks,” he says.

His key advice? Sell it with science. Sell the medical benefits. Promise to school the communities in proper usage. All of that online organization, Plazola cautions, is just 20 percent of the work that Decriminalize Nature Oakland does. The other 80 percent? Stamets-style education in the community, giving guidance for would-be trippers to use the mushroom safely, subtly, and effectively.

Like it or not, the psilocybin decriminalization wave may be about to wash across America. It has young, energized, and connected activists behind it. Recreational licenses in dispensaries may be in our near future. And if we’re going to enter this world, we can either allow another vast mega-business of mushroom concoctions, marketed in the same overboard manner as THC and CBD. Or we can bake in a more cautious, less commercial, microdosing-based approach from the start.

And because that is the choice ahead of us, it’s a good thing that Stamets is out there, the most well-connected node in this mycelial network of change.

BURNING KNOWLEDGE

Stamets’ audience at Lightning in a Bottle.

MICHAEL DRUMMOND

On stage, Stamets likes to talk about the book burning that looms large in his origin story.

Growing up in conservative small-town Ohio, Stamets had no clue about the power of mushrooms. Not until his brother happened to get interested in the topic in the wake of a seminal Life magazine article on psilocybin ceremonies in Mexico. Paul had asked to borrow his brother’s book on psychedelic substances, then loaned it out again to a similarly interested friend. The friend awkwardly admitted that his father had burned the book.

“I’d like to thank that man now,” Stamets says to applause, “for putting me where I am today.”

Insistent that he was now going to study the very knowledge that was denied him, Stamets became a mushroom researcher (alongside a young Andrew Weil). He was most definitely in it for the psilocybin — “your suspicions about me are true,” he says to laughter when showing a photo of young him, a lanky, long-haired hippy brewing mushroom tea on a stove.

But over time, that changed. As with other users of psilocybin (Pollan calls it and other psychedelics “anti-addictive”), Stamets ramped down his usage. Not that he shunned it, he just became more interested in the questions and applications that swirled around this marvelous mushroom world.

He was fascinated by a hypothesis commonly called the “Stoned Ape” theory, popularized in the 1990s by botanist Terrence McKenna and his brother Dennis. It turns out that psilocybin mushrooms grow prodigiously in the dung of many African mammals, which were right in the path of our distant ancestors as they tracked game by its spoors.

You’re hunting. You’re hungry. Why wouldn’t you eat? After all, homo sapiens is only one of 22 primates that discerns and eats mushrooms of various effects. “We now know that [magic] mushrooms help you overcome the conditioned fear response,” says Stamets. “You’d eat them after a traumatic experience, you’d bond, you’d strategize.”

The Stoned Ape hypothesis is a controversial one. Those who support it point to a couple of recent studies that suggest that psilocybin may induce “neurogenesis,” or growth of nerves in the brain. Homo sapiens seem to have experienced a doubling in brain size between about 800,000 and 200,000 years ago, but the jury is still out on what caused that.

That era was one of rapid climate change, as is ours. This time around, Stamets insists in his airier moments, mushrooms can help induce the kind of neurogenesis that can help us invent and organize our way out of climate disaster. But in his less airy moments, he has a more concrete way out of the carbon dioxide mess.

Fungal networks in the ground make up the bulk of carbon storage in forests, Stamets explains, transforming into uber-Bill Nye again. Indeed, scientists in Sweden were surprised by this, according to a a 2013 soil study; they were expecting dead tree matter to shoulder the carbon burden.

But as Stamets says, “dead mycelium can store carbon for hundreds of thousands of years. So the most important communication I can give to people is, invest in mycelium — both in terms of soil science and in terms of consciousness.”

Is that why he was here at Lightning in a Bottle, I asked? Was that why he goes to Burning Man? Is he trying to educate America’s music and art festivals, to reshape the future of society through cutting-edge youth culture gatherings?

Perhaps, but not entirely. “I’m 64 years of age, but man, I love electronica,” he says, wearing a broad but sincere grin.

And with that, Stamets dances away in his utilikilt, into the bright mushroom morning.