by Adam Gopnik: With greater longevity, the quest to avoid the infirmities of aging is more urgent than ever…

ging, like bankruptcy in Hemingway’s description, happens two ways, slowly and then all at once. The slow way is the familiar one: decades pass with little sense of internal change, middle age arrives with only a slight slowing down—a name lost, a lumbar ache, a sprinkling of white hairs and eye wrinkles. The fast way happens as a series of lurches: eyes occlude, hearing dwindles, a hand trembles where it hadn’t, a hip breaks—the usually hale and hearty doctor’s murmur in the yearly checkup, There are some signs here that concern me.

To get a sense of what it would be like to have the slow process become the fast process, you can go to the AgeLab, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, and put on agnes (for Age Gain Now Empathy System). agnes, or the “sudden aging” suit, as Joseph Coughlin, the founder and director of the AgeLab describes it, includes yellow glasses, which convey a sense of the yellowing of the ocular lens that comes with age; a boxer’s neck harness, which mimics the diminished mobility of the cervical spine; bands around the elbows, wrists, and knees to simulate stiffness; boots with foam padding to produce a loss of tactile feedback; and special gloves to “reduce tactile acuity while adding resistance to finger movements.”

Slowly pulling on the aging suit and then standing up—it looks a bit like one of the spacesuits that the Russian cosmonauts wore—you’re at first conscious merely of a little extra weight, a little loss of feeling, a small encumbrance or two at the extremities. Soon, though, it’s actively infuriating. The suit bends you. It slows you. You come to realize what makes it a powerful instrument of emotional empathy: every small task becomes effortful. “Reach up to the top shelf and pick up that mug,” Coughlin orders, and doing so requires more attention than you expected. You reach for the mug instead of just getting it. Your emotional cast, as focussed task piles on focussed task, becomes one of annoyance; you acquire the same set-mouthed, unhappy, watchful look you see on certain elderly people on the subway. The concentration that each act requires disrupts the flow of life, which you suddenly become aware is the happiness of life, the ceaseless flow of simple action and responses, choices all made simultaneously and mostly without effort. Happiness is absorption, and absorption is the opposite of willful attention.

The annoyance, after a half hour or so in the suit, tips over into anger: Damn, what’s wrong with the world? (Never: What’s wrong with me?) The suit makes us aware not so much of the physical difficulties of old age, which can be manageable, but of the mental state disconcertingly associated with it—the price of age being perpetual aggravation. The theme and action and motive of King Lear suddenly become perfectly clear. You become enraged at your youngest daughter’s reticence because you have had to struggle to unroll the map of your kingdom.

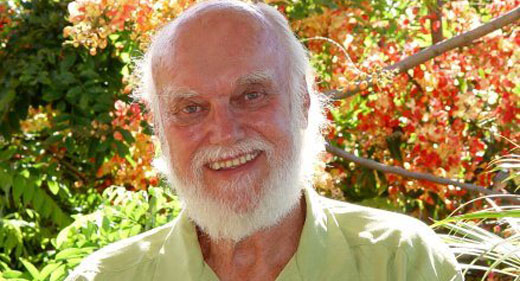

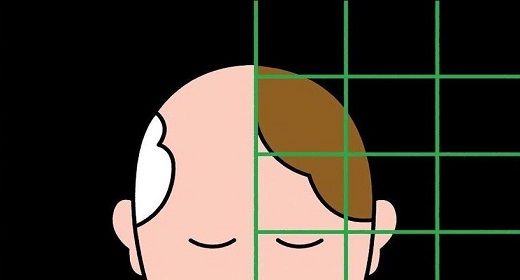

The AgeLab is designed to alleviate this progression. It exists to encourage and incubate new technologies and products and services for an ever-larger market of aging people. (“Every eight seconds, a baby boomer turns seventy-three,” Coughlin observes.) Coughlin, who is in his late fifties, is the image of an old-fashioned American engineer-entrepreneur; he is bald in the old-fashioned, tonsured, Thurber-husband way, wears a bow tie and heavy red-framed glasses, and, walking a visitor through the lab, suggests a cross between Mr. Peabody and Q, from the Bond films, showing you the latest gadgets. His talk is crisply aphoristic and irrigated with an easy flow of statistics: each proposition has its instantly associated number.

“Where science is ambiguous, politics begins,” he says. “In the designation of some states, an older driver is fifty, in some eighty—we don’t even know what an older driver is. That ambiguity is an itch I wanted to scratch. Over the past century, we’ve created the greatest gift in the history of humanity—thirty extra years of life—and we don’t know what to do with it! Now that we’re living longer, how do we plan for what we’re going to do?”

Having picked the mug up, the suit wearer finds that setting the mug down gently on a nearby table is also a bit of a challenge. So is following Coughlin from room to room as he narrates all that the AgeLab has learned.

“Here’s a useful model for you,” he says. “From zero to twenty-one is about eight thousand days. From twenty-one to midlife crisis is eight thousand days. From mid-forties to sixty-five—eight thousand days. Nowadays, if you make it to sixty-five you have a fifty-per-cent chance you’ll make it to eighty-five. Another eight thousand days! That’s no longer a trip to Disney and wait for the grandchildren to visit and die of the virus you get on a cruise. We’re talking about rethinking, redefining one-third of adult life! The greatest achievement in the history of humankind—and all we can say is that it’s going to make Medicare go broke? Why don’t we take that one-third and create new stories, new rituals, new mythologies for people as they age?”

The agnes suit is one of many instruments and appliances—or “cool toys,” as they are more technically known—that can be found in the AgeLab’s glass-walled halls and cubicled corridors, ready to entertain visiting writers, and to instruct visiting entrepreneurs. There is the driving simulator, specially fitted to track the driver’s eye movements as they flit back and forth from the dashboard to the horizon. (“With its new technologies, like navigation systems, the automotive industry is asking people to change fifty years of driving habits in ten minutes without instruction,” Coughlin says.) There is Paro, a robotic baby seal, from Japan, which bleats and moves its head, and is designed to act as a comfort to aging people, particularly Alzheimer’s patients struggling with the “sundown” moment at day’s end, when confusion and restlessness become acute. (“It’s a seal, rather than a dog or a cat, because people have great experiences with dogs and cats, and even Alzheimer’s patients can spot the eerie non-resemblance,” Coughlin says. “Having no experience of seals, we accept Paro as he is.”) There are mobile robotic nurses made for elderly care, and broad red upholstered chairs made for elderly rears. There are large research displays showing photographs of drivers, their faces embedded with sensors, and the varieties of “Glance Classification” that can, when analyzed, lead to “Crash Avoidance.” (“The ratio between confident decisions and correct confident decisions can be a story of life or death on the highway,” Coughlin explains.) And there are displays of word clouds associated with aging, showing the significant difference between the terms with which women imagine their post-career lives (Freedom, Time, Family) and those which men use (Retirement, Relax, Hobbies).

The work of the AgeLab is shaped by a paradox. Having been established to engineer and promote new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged, the AgeLab swiftly discovered that engineering and promoting new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged is a good way of going out of business. Old people will not buy anything that reminds them that they are old. They are a market that cannot be marketed to. In effect, to accept help in getting out of the suit is to accept that we’re in the suit for life. We would rather suffer because we’re old than accept that we’re old and suffer less.

This paradox is, well, old. Heinz, back in the nineteen-fifties, tried marketing a line of “Senior Foods” that was, essentially, baby food for old people. It not only failed spectacularly but, as Coughlin puts it, poisoned an entire category. The most perverse of these failures is perhaps that of the pers, or personal-emergency-response system, a category of device—best known for the hysterically toned television ad in which an elderly woman calls out, “I’ve fallen and I can’t get up!”—designed as a neck pendant that summons emergency services when pressed. It is simple and effective. “The problem is that no one wants one,” Coughlin says. “The entire penetration in the U.S. of the sixty-five-plus market is less than four per cent. And a German study showed that, when subscribers fell and remained on the floor for longer than five minutes, they failed to use their devices to summon help eighty-three per cent of the time.” In other words, many older people would sooner thrash on the floor in distress than press a button—one that may summon assistance but whose real impact is to admit, I am old.

“We buy products not just to do jobs but for what they say about us,” Coughlin summarizes. “Beige or light-blue bracelets or pendants say ‘Old Man Walking.’ ”

The AgeLab has rediscovered the eternal truth that identity matters to us far more than utility. The most effective way of comforting the aged, the researchers there find, is through a kind of comical convergence of products designed by and supposedly for impatient millennials, which secretly better suit the needs of irascible boomers. The best hearing aids look the most like earbuds. The most effective persdevice is an iPhone or an Apple Watch app.

Such unexpected convergences have happened in the past. Retirement villages came to be centered on golf courses, Coughlin maintains, not because oldsters necessarily like golf but because they like using golf carts. It’s the carts that supply greater mobility in and around the village. The golf comes with them. This process of “exaptation” has now accelerated. TaskRabbit and Uber and Rent the Runway—services that provide immediate help for specific problems—are especially valuable for an aging population.

“The dominant paradigm is that older people don’t want new technology,” Coughlin says. “But take the microwave oven! It couldn’t have been better designed for people who live by themselves. It’s a perfect example of what I call ‘transcendent design’—not made for older people, but ideal for them. We’re doing a lot of work in the on-demand economy, which was made for millennials but is working better for boomers. Meals are delivered—these are amazing, assisted-living services that can come to anyone’s house. Older women in particular are saved from microdeficiencies in their diet. So, while the millennials want them for convenience, the boomers want them for care for their parents, or themselves.”

Coughlin hates what he calls “the narrative,” according to which new tech appeals to newer people: “Startup money goes to youngsters because that’s what startup entrepreneurs are supposed to look like, and the products are designed for kids because that’s what startup products are meant to look like.” In his view—detailed in his book “The Longevity Economy”—the narrative, more than any rational calculation of profit, accounts for the technological gap. “There’s no reason for this enormous prejudice in favor of youthfulness in Silicon Valley and the tech industry,” he says. He also hates the misallocation of resources based on mere myths. “We have a belief that we send out our elderly to institutions. The fact of the matter is that less than ten per cent of the elderly go into nursing homes or assisted living. The senior-housing industry is building inventory meant for seniors, but eighty-seven per cent of retirement-age people want to stay in the same home where they have the three ‘M’s: marriage, mortgage, and memories. The problem is that they can’t. Not when the model is a two-story house with a bedroom and the bathroom upstairs. If we can solve the stairs problem, we won’t need new housing.”

Coughlin says that having simple answers to two questions can determine whether you’re going to age well in place: “Who’s going to change the light bulb, and how are you going to get an ice-cream cone? Little tasks become sources of high friction. It’s not that you can’t climb the ladder to change the light bulb. But for the first time you are going to have someone yelling at you, ‘You’re going to fall and break your neck!’ That’s the problem of aging we have to tackle, not building more old people’s homes or senior villages.” It’s the failure of industry and engineering to address the actual problems of aging—the problems summed up by the aggravations of the agnes suit—that makes Coughlin impatient with scientific speculations about extending life. “We’ve already extended life! What we need is not to put off death a little longer but to write a new narrative of aging as it could be.”

Aging has no point; it is the infuriating absence of a point. Having reproduced ourselves externally, we fall down on replicating ourselves internally. The processes of cellular replication that allow us to be boats rebuilt even as they cross the ocean cease acting efficiently, because they have no evolutionary reward for acting efficiently. They are like code monkeys in a failing tech business: they can mess up everything, absent-mindedly forget to code for the color of our hair or the elasticity of our skin, and no penalty is exacted for the failure. We’ve already made all the kids we are going to make.

That, at least, is the classic explanation of why we age, proposed by the British Nobel laureate Peter Medawar, in the nineteen-fifties. Once we have passed reproductive age, the genes can get sloppy about copying, allowing mutations to accumulate, because natural selection no longer cares. And so things fall apart. The second law of thermodynamics gets us all in the end. The car or the Cuisinart works for a decade, breaks down, and can’t be fixed; rust never sleeps, and we do.

And yet some trees go on for centuries, collecting rings, growing older without really aging. Some species—though those are often hard-to-track creatures, like Arctic sharks—may live for centuries. Even if aging at some speed is ultimately inevitable, what happens when we age is far from self-evident.

It may be that the real trick is not how much we age but how much we don’t. Human beings are outliers: we live much longer than other creatures of our size, defying the general truth that smaller animals live shorter lives than bigger ones. (Not that we should take too much pride in our defiance; another great defier is the naked mole rat, the world’s ugliest animal, which often lives for absurdly long periods and scarcely seems to age at all, although one might ask how anyone but another naked mole rat could tell.) Those extra thirty years of life, though won by advances in medicine and public health, are winnable because, given a little chance, we just go on. The big question of human aging then becomes not why we fall apart but why nature lets us hold together for so long.

One evolutionary rationale is that there is something essential to human groups, with the slowly unfolding infancy of their young, in keeping the old folks around even when they can’t make more young folks. Old folks are repositories of extended cultural memory: it would seem to be advantageous to have a few senior citizens around who know what to do, so to speak, when winter comes. Evolutionary biologists tend to doubt whether nature cares about the fitness of groups, rather than the fitness of individuals, but the model of “kin selection”—which gives weight to the fact that helping my relatives helps preserve my genes—suggests that there might be evolutionary advantages in having grandmothers around to take care of kids and remember where the fish go every twenty years. (Then again, people who do have grandparents around to remind them what they’re doing wrong would probably suspect that killing off the oldsters early might actually make for more success, or at least more serenity.) People might not have a death sentence in their genes.

And so elsewhere in Cambridge, notably in certain genetic labs at Harvard, the chairs and seals and exaptated services of the AgeLab are regarded as mere Band-Aids on the problem to be solved. Here, there are whispers of undying yeast, tales of eternally young mice, rumors of rejuvenated dogs, and scientists who stubbornly insist that age is an illness to be treated like any other.