by Laura Fedi: Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was better known as a sculptor when Pope Julius II tapped him to illuminate the Sistine Chapel…

Known to the world as Michelangelo, the Florentine was just 24 when he sculpted his renowned “Pietà,” a tender depiction of the Virgin Mary cradling the lifeless body of her son. His towering “David” revealed his mastery of sculpting the human form.

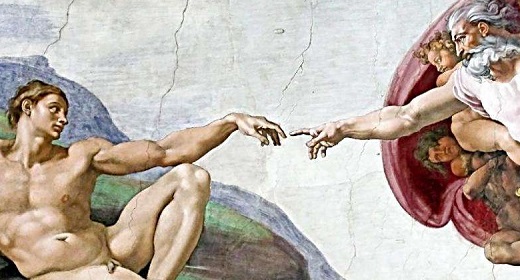

For all the skill and beauty of his work with a chisel, it is perhaps his work with a brush for which he is remembered most of all. The bold colors and striking composition of his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel still awe viewers with their power and emotion. The Sistine ceiling and the “Last Judgment” stand as a testament to Michelangelo’s genius as a painter and evolution as an artist.

Picture of the cupola of St. Peter’s Basilica

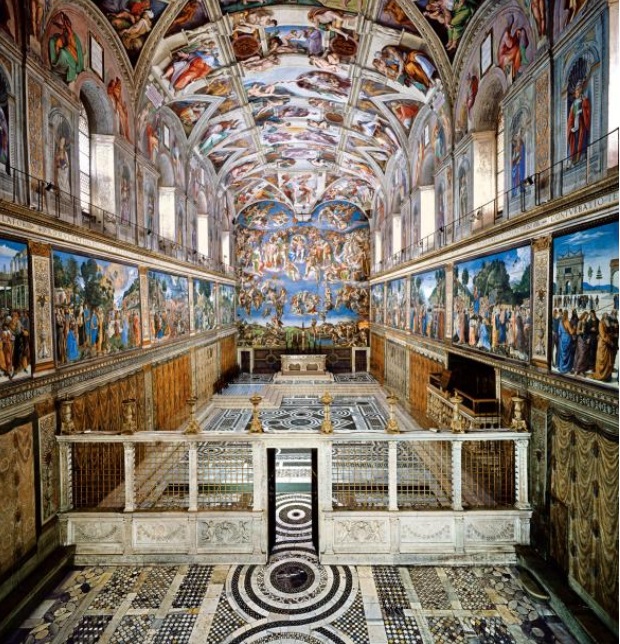

Picture of the interior of the Sistine Chapel

INSIDE LOOK

The cupola of St. Peter’s Basilica (left), designed by Michelangelo, was uncompleted at his death. Next to it, the Sistine Chapel seems unremarkable—at least from the outside. Opposite…

PHOTOGRAPH BY ARCHIVIO FOTOGRAFICO MUSEI VATICANI

The Sistine ceiling was completed in 1512, a little before the Protestant Reformation. On the west wall, the “Last Judgment” fresco was unveiled nearly three decades later, as the effects of Martin Luther’s revolution spread across Europe. Both works reflect the spirit and themes of the times: the Renaissance love of the human body; the tension between wealth and faith; and, above all, an explosively vibrant rendering of the great stories of the Bible.

Summons by the Pope

In 1503 a new pope was appointed: the very worldly Pope Julius II, a self-declared lover of power, war, and art. Under his rule, Rome came to resemble a magnificent salon with a host of artists and architects at work on different projects. The precocity of the young Michelangelo—who, at Julius’s accession was sculpting the astonishing 17-foot-high “David” in Florence—reached the ears of the pontiff. In 1505 Julius summoned him to Rome to work on his future tomb, a commission that soon extended into a remodeling of St. Peter’s Basilica itself.

CONSPIRACY THEORY

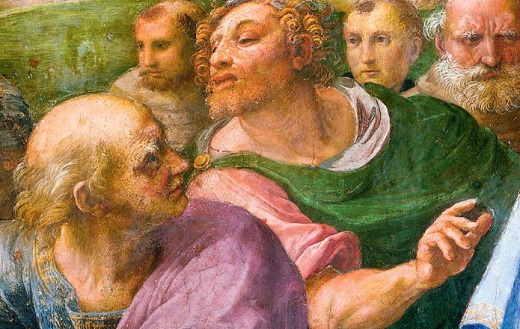

Detail from an oil painting by Raphael showing the dispute between Bramante and Pope Julius II.

PHOTOGRAPH BY THE RAPHAEL ROOMS, VATICANI, ROME

Michelangelo wrote: “All the discords that arose between Pope Julius and me were owing to the envy of Bramante [Pope Julius’s chief architect] and of [the painter] Raphael.” Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo’s first biographer, had a different theory: Bramante put forward Michelangelo’s name to paint the Sistine ceiling, but did so out of spite, calculating that when Michelangelo began to paint, his lack of expertise would be exposed and his career ended. Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, also follows this argument. Michelangelo was dubious of his abilities as a painter, so the theory may not be far-fetched. History has shown, however, that Bramante’s tactic spectacularly backfired.

The papal tomb, which Michelangelo biographer Andrew Graham-Dixon has called “a megalomaniac fantasy, an obscene monument to ego, pride, and power,” was nonetheless a plum commission. After a run-in with the pope over non-payment for materials, however, Michelangelo left Rome in disgust. Julius, realizing his mistake, insisted that the artist continue working for him and ordered him back to work on an enticing new project: the frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

When Michelangelo returned to Rome in 1508, Donato Bramante, the pope’s chief architect, and a sworn enemy of Michelangelo, was busy working on the new Basilica of St. Peter. In 1546, when he was an old man, Michelangelo would be appointed chief architect of the new St. Peter’s—which was finally completed in 1615—but this lay far in the future. Raphael, another rival, was starting work on frescoes in the pope’s private chambers, and next to such grand projects, the Sistine Chapel, with its plain exterior, might have seemed a lesser project.

Obverse of a medal commemorating the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica. British Museum, London

PHOTOGRAPH BY SCALA, FLORENCE

Its outer appearance was deceptive, for it was a special building inside: Restored a few decades before by Pope Sixtus IV (for whom it is named) it was the place of worship for the Papal Chapel, the part of the Vatican dedicated to assisting the pontiff in his spiritual functions. Today it is the setting of the conclave, where the cardinals choose a new pope. Pope Julius was adamant that he wanted only one artist to complete its decoration, and despite their previous altercation, he gave Michelangelo the job.Moments of doubt

Bramante was quick to complain how lacking in experience Michelangelo was for such an extraordinarily challenging project. He had a point: Michelangelo had learned the craft of mural painting in the studio of Domenico Ghirlandajo in Florence, where he was an apprentice at age 13. But he had never really worked as a painter, having moved instead into sculpting for the Medici family at age 15. He was commissioned to paint a battle fresco for Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, and although some of his cartoons for this work have survived, the frescoes themselves were never painted. On various occasions, Michelangelo spoke of his own shortcomings, warning that his real talent was not for painting at all but for sculpture.

Frescoes by other artists had already been painted on the walls. Michelangelo was to paint the whole ceiling, a structure roughly 132 feet long and 44 wide. Filling an expanse of nearly 6,000 square feet with frescoes would have daunted even the most experienced of painters. Even so, the Florentine held his nerve, and pushed for the best possible deal. In May 1508 a proposed plan was dismissed by the artist, who thought it “a poor thing.” In the next iteration he was given carte blanche.

Picture of six of the nine panels of the Sistine Chapel ceiling

The nine panels of the Sistine Chapel ceiling depict iconic scenes from the Old Testament, but perhaps Michelangelo’s most famous imagery can be found in the first six panels, which show the creation of the heavens, the earth, and humanity according to the first three chapters of Genesis.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ARCHIVO FOTOFRAFICO MUSEI VATICANI

‘

The scope was breathtaking: The vault itself is dedicated to episodes from the Old Testament, divided into three sections: the Creation, the Garden of Eden, and the Flood. The space left over was also filled with painting. In the semicircular lunettes above the windows, and in the roughly triangular spandrels, were placed biblical figures who preceded Christ. Panels above them were reserved for prophets who had, according to Christian scripture, foretold Christ. Faithful to the Renaissance classical spirit, Michelangelo included sibyls in this prophetic tradition, including the Libyan Sibyl. The pendentives at the four corners of the ceiling recount episodes in the salvation of Israel.

One notable aspect of Michelangelo’s art is how his figures representing women often have male physiology.

Challenges and setbacks

Vast technical problems beset the artist at the outset. In his book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Giorgio Vasari, the 16th-century architect, artist, and writer, records some of Michelangelo’s trials. The fresco technique Michelangelo used, which requires applying washes of paint to wet plaster, left no room for error or revisions. Time was of the essence.

Once sketches were prepared, they had to be divided up into sections that could be finished in one day. If he attempted to do too much at once, the plaster would dry out and would not absorb the colors. Once a section of wall had been chosen, it was prepared first with whitewash and then with plaster made from a mixture of pozzolanic ash, lime, and water. The drawing was transferred to the plaster, and then the colors were added immediately.

Michelangelo brought a few trusted artists from his native Florence to work with him. But the Florentine plaster recipe they preferred did not work with the Roman materials and climate. Patches of mildew sprouted, and the paint had to be removed and reapplied, which slowed progress.

In the eighth panel of the Genesis sequence, Michelangelo depicts people’s useless attempts to escape the rising floodwaters. He contrasts their fear and panic with Noah’s ark, which sits serenely in the background, a place of quiet salvation.

Meanwhile, Julius became so impatient for Michelangelo to complete the project that, according to Ascanio Condivi, the artist’s biographer, the pope threatened to throw the painter off the scaffolding and on one occasion actually hit him “with a stick.” Finally, in 1512, after four years of physical and creative dedication, Michelangelo finished his monumental work.

Unlike traditional hierarchical depictions of the Last Judgment, Michelangelo has chosen a more dynamic treatment of the subject where everything flows around the central figure of Christ. Angels lift souls from their graves on the left, judgment is rendered in the center, and the damned are dragged to hell on the right. Michelangelo’s depiction of hell was deeply influenced by Dante’s Inferno, and several figures from the work appear here. Beneath Christ, the ferryman Charon guides his boat of sinners across the river Acheron where the fiendish figure of Minos waits on the other side.

Return to the chapel

Michelangelo’s contribution to the Sistine Chapel, however, was not complete. More than 20 years later, in 1536, Pope Paul III commanded that he paint a fresco of the Last Judgment on the wall behind the altar. Michelangelo, then over 60, reluctantly accepted. When the work was finished in 1541, Paul III is said to have fallen to his knees in prayer.

In the decades since the completion of the ceiling in 1512, Paul III’s predecessors, Leo X, Adrian VI, and Clement VII, had been engulfed by the Reformation. Ironically, Luther’s revolution had begun in 1517 as a protest against the selling of indulgences to pay for the huge costs of Rome’s art spree. Since then, swaths of northern Europe had become Protestant.

The tortured religious circumstances of Europe at the time inevitably color Michelangelo’s last contribution to the chapel. Filling the whole of the wall, the fresco is dominated by Christ who dispenses judgment. The naked figures that swarm against the lapis lazuli sky surround Christ; they are a combination of saints and martyrs. Michelangelo painted these fleshy, muscular bodies with a heft and weight not present in the figures on the ceiling.

Unlike traditional hierarchical depictions of the Last Judgment, Michelangelo has chosen a more dynamic treatment of the subject where everything flows around the central figure of Christ. Angels lift souls from their graves on the left, judgment is rendered in the center, and the damned are dragged to hell on the right. Michelangelo’s depiction of hell was deeply influenced by Dante’s Inferno, and several figures from the work appear here. Beneath Christ, the ferryman Charon guides his boat of sinners across the river Acheron where the fiendish figure of Minos waits on the other side.

The Last Judgment

By the middle of the 16th century the orthodoxy of the Counter-Reformation was strengthening. When Pius IV became pope in 1559, the years of hedonistic, art-loving popes were long past. The nudity in the “Last Judgment” was now seen as indecent. In 1562 the Council of Trent approved a decree regulating the use of images in churches, and Pius agreed that the nudity must be covered. Soon after Michelangelo died at age 88 in 1564, artist Daniele da Volterra was the first to censor the “Last Judgment,” and over the centuries, nearly 40 more coverings were added.

Gianluigi Colalucci works on the figure of St. Bartholomew during the 1990s restoration of the “Last Judgment.”PHOTOGRAPH BY VITTORIANO RASTELLI/CORBIS/GETTY IMAGES

In the 1980s and 1990s a major restoration of the Sistine Chapel frescoes revealed the vibrant colors that had been obscured over time. Michelangelo’s mastery of the human form was also revealed by removing many of the drapes added by censors. When seen today, the Sistine frescoes never fail to astonish with their beauty and complexity. They reveal two distinct phases of Renaissance art as well as two phases of Michelangelo’s artistic evolution.